There is a special job in the NICU that is “Family Support Specialist.” This person has the opportunity to walk alongside families through their NICU stay with the primary purpose of enhancing their relationship with their precious baby. While the role may be adapted to meet institutional needs, the overall goal is facilitating healthy bonds and supporting infant mental health in the NICU. Infant mental health refers to how well a child develops socially and emotionally from birth to three years old. By observing, assessing and ultimately supporting the optimal development of these areas, we are preventing and treating mental health problems of very young children and families and laying the groundwork for healthy development.

The field of infant mental health, much like the NIDCAP, is multidisciplinary, and professionals from different disciplines may have the lens to support these relationships. That said, becoming a NIDCAP Professional enhanced my observational skills and provided me with an extremely useful tool to engage with families and “wonder with” more fully. It is my hope that as Newborn Intensive Care Units embrace family involvement, that NIDCAP Family Support Specialist will become an essential part of the NICU team.

I began my social work career as a Family Support Specialist working for the March of Dimes at Northwestern Prentice Women’s Hospital. At the time, the March of Dimes’ program focused largely on family education through providing materials and classes and hospital-based volunteer and parent mentor management. Family support specialists were prohibited from touching any NICU patient for liability reasons and focused on more macro work. We hosted events that brought families together or encouraged family involvement like Kangaroo-a-thons.

To enhance my skills I began postgraduate studies in Infant Mental Health at the Erikson Institute where I learned more about supporting parent-infant relationships through promotion, prevention and intervention. It helped me further develop a relational lens for my social work practice, and learn the significance of reflective supervision to address the feelings and experiences I had as a working professional.

There is a whole body of research discussing the difference between reflective supervision and other supervision models. At the core of reflective supervision is the belief that all relationships are important. That is, the relationship between the practitioner and their supervisor, the practitioner and the parent/infant they serve and of course the relationship between the parent and infant; All these relationships impact one another in a parallel process. Reflective supervision should be offered to the interdisciplinary team working with NICU Families. When done well, reflective supervision highlights strengths while partnering to address vulnerabilities. With shared power, reflective supervision creates a more ethical practice and encourages the practitioner to create and hone self-knowledge, cultural humility and critical thinking.

With my newfound understanding of infant mental health and interest in reflective work, my next destination was UI Health NICU where, as a Family Support Specialist, I had more versatility to define the scope of this position. Perhaps the most inviting aspect of this job was that I would become NIDCAP trained under Jean Powlesland. Working at UI Health, I could utilize my new infant mental health relational lens and my clinical social work skills to more individually assess and support families. However, NIDCAP was the glue that held all the aspects of my job together and made this an Infant Mental Health position.

NIDCAP allowed me to better see through the eyes of the infant and interpret the behavior of the premature or sick baby with the family and nurse. For me, NIDCAP is the most relevant and effective infant mental health tool for the NICU. Premature babies communicate differently than full term babies and sometimes parents can interpret these cues as rejection. Premature parents are forced to communicate in different ways than they would otherwise in the NICU due to the physical and emotional barriers. These barriers make it difficult for parent and baby to become attuned and learn to communicate with each other. This warrants infant mental health observation and intervention to bridge the communication gaps that exist in the early days so that they can create secure attachments and healthy relationships.

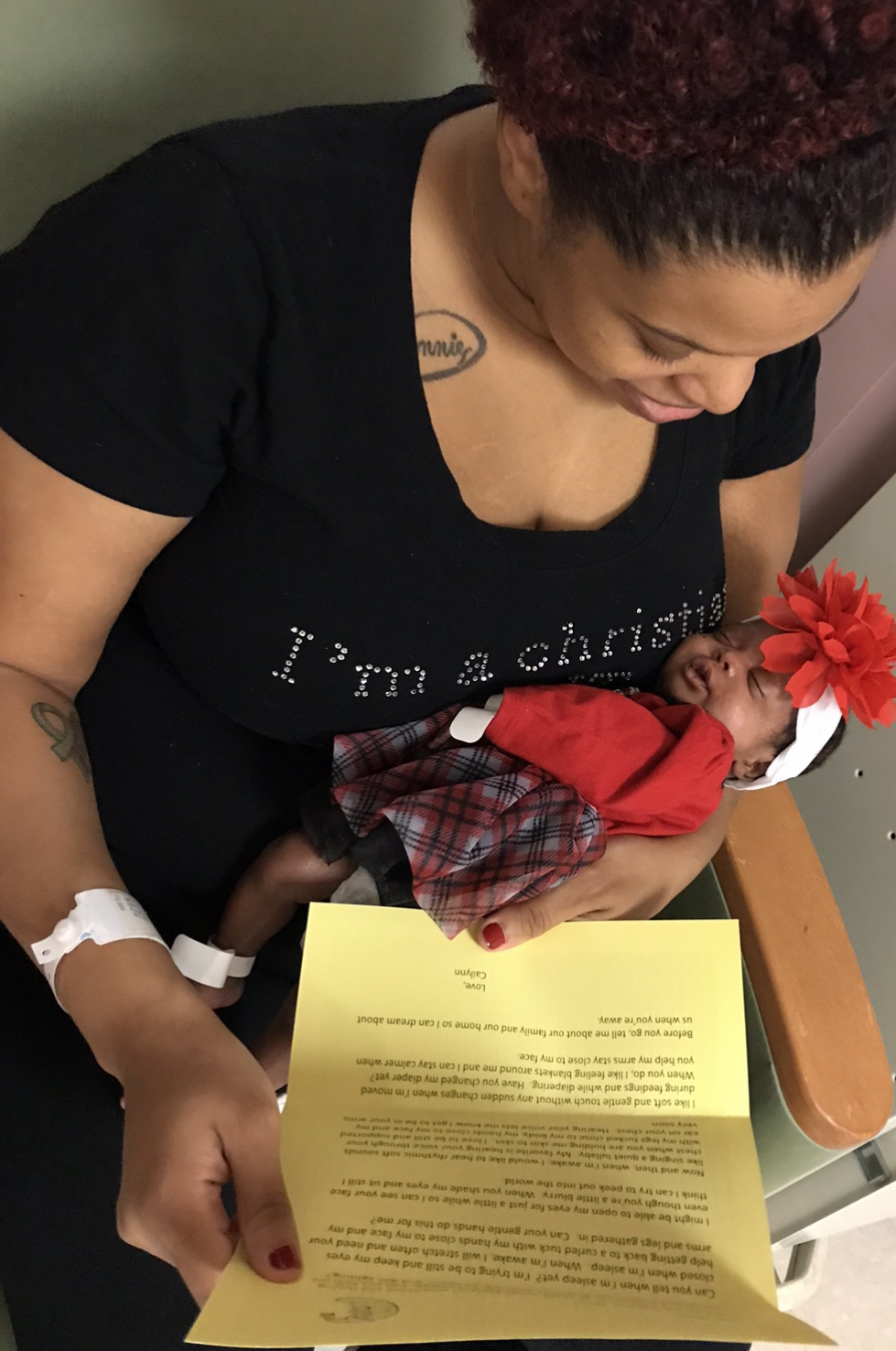

When I met with premature parents after their baby was born, I would use a simple assessment to start to gage how much they have begun to think about their baby as an individual. The Fussy Baby Network recommends asking, “Tell me three words to describe your baby.” Often, parents struggled to come up with words that describe individual qualities/characteristics and will land on some more common NICU descriptions like “loved, strong or fighter.” More times than not, they could not come up with three words. This is an easy way to gage how their relationship grows (or doesn’t) and how well they begin to know their baby over time. From here, information from NIDCAP observations can be integrated into Baby Love Letters. Every two weeks or so, parents would receive a letter written from their baby to them. The letters included both sentimental lines and developmentally appropriate and individually assessed ways to interact and support the baby.

In the micro work with families, one of the most useful interventions requires very little clinical skill but a tremendous amount of patience and compassion. Family Support Specialists learn the art of just being with and holding space for the infant and family. In some of the most difficult circumstances there is not anything to do or say but to just “be with.” When I allowed myself to be comfortable with silence, I found some of the most authentic moments unfold. I can remember distinctly a “difficult mom” fall into my arms, heartbroken and afraid, no need for words. It was powerful what she communicated to me so much so that when I think about her now, I can still feel some of her sadness in my own heart.

There are times, of course, when assessments (and words) are helpful. There were even some parents who were ready and open to receiving more classic mental health therapy in the NICU. Outside of NIDCAP, I found that depending on my relationship with the family, questions from Angels in the Nursery or ACES could help me better gage how to support the parent/infant relationship. But often, just touching base by asking “What has this been like for you?” and “What have you noticed about your baby recently?” was enough intervention in the NICU to start meaningful conversations.

In the macro work with families, NICU Family Support Specialists provide opportunities for families to meet and interact through programs and support groups. I observed that parents who actively participated in Family Support programming were better able to describe their baby at the end of their NICU stay than parents who were not active. Parents had an opportunity to more fully integrate what they were feeling and learning by creating relationships with other families in the NICU.

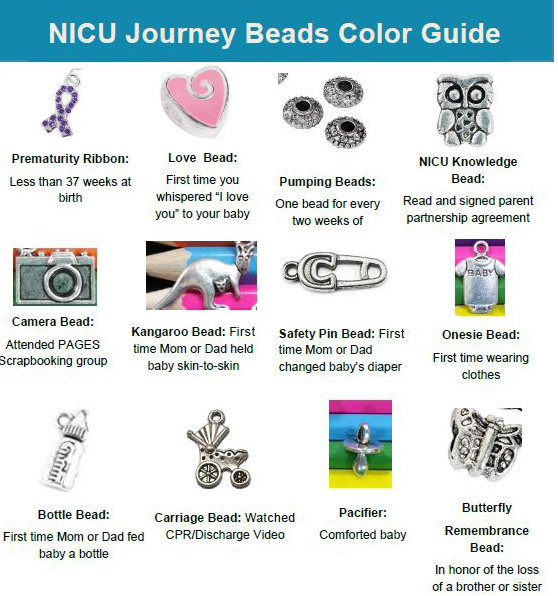

Weekly the NICU would offer scrapbooking where parents could print off photos of their baby and create keepsake pages to show their journey. Likewise, bimonthly parents had the opportunity to participate in the “Journey Beads” program where they created charm bracelets where each charm symbolized a milestone of some sort creating a tangible memento of their and their baby’s NICU experience. In addition to more structured groups, we held dinners and holiday events. These programs can be tailored to different NICU needs but the coordination of opportunities for parents to meet and talk about their baby with current families is the goal.

Working as the Family Support Specialist with Jean Powlesland was an extraordinary professional experience; one that I look back on with gratitude. The position is created to be flexible and can be tailored to the professional’s skill set but always with the focus of supporting early relationships in the NICU. While every NICU professional should be holding the parent/infant relationship at the center of their work, it is especially significant to have one person in the NICU to focus entirely on the baby and family experience through NIDCAP assessment, Infant Mental Health intervention and reflective practice consultation.

Jessica Bowen

Licensed Clinical Social Worker, infant and early childhood mental health credentialed and a NIDCAP professional

References

Finding Your ACE Score. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ncjfcj.org/publications/finding-your-ace-score/

Narayan, A. J., Ippen, C. G., Harris, W. W., & Lieberman, A. F. (2017). Assessing Angels In The Nursery: A Pilot Study Of Childhood Memories Of Benevolent Caregiving As Protective Influences. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(4), 461–474. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21653

https://www.aaimhi.org/resources/reflective-supervision/BestPractice_ReflectiveSupervision_2015.pdf

Van Horn, P., Lieberman, A. F., & Harris, W. W. (2008). The angels in the nursery interview. University of California, San Francisco, Department of Psychiatry.